29.02.2024.

Reconciliation by Stealth: How People Talk about War Crimes – review

Denisa, RECOM, Reconciliation by StealthIn Reconciliation by Stealth: How People Talk about War Crimes, Denisa Kostovicova considers how best to achieve reconciliation in post-conflict societies, focusing on case studies from the Balkan region. Arguing for a process-oriented, dialogic and empathetic approach, Kostovicova reimagines conventional transitional justice mechanisms, writes Ajla Henic.

As Kalyvas suggests in The Logic of Violence in Civil War, violence is better understood as a process than a discrete act; it follows that reconceptualising reconciliation as a process rather than an ultimate objective is vital to our understanding of post-conflict dynamics. In order to be meaningful, transitional justice mechanisms aimed at achieving recognition and reconciliation must consider this ongoing process comprehensively, as Denisa Kostovicova shows in Reconciliation by Stealth: How People Talk about War Crimes.

Kostovicova, an outstanding scholar in post-conflict reconstruction and post-conflict justice processes in the Balkans, raises questions and reflections regarding societies navigating the post-conflict transformation. In conflicts characterised by identity aspects, violence often serves to further solidify these identities, perpetuating an ethnonationalist understanding of post-conflict society. The prevalence of polarisation, a stark reality in societies institutionally divided by peace treaties, further complicates the journey towards reconciliation.

“Kostovicova introduces ‘reconciliation by stealth’, an emancipatory concept within transitional justice processes that foregrounds the necessity for discursive solidarity. By analysing how people talk about war crimes, we can subtly advance the idea of reconciliation as a process.”

Kostovicova introduces “reconciliation by stealth”, an emancipatory concept within transitional justice processes that foregrounds the necessity for discursive solidarity. By analysing how people talk about war crimes, we can subtly advance the idea of reconciliation as a process. The author is acutely aware of the various pejorative interpretations of this complex concept, ranging from moral relativism to the potential belittlement of suffering, foreign imposition, instrumentalised usage by local authors, and scholarly scepticism (126, 127). However, the author convincingly contends that truth commissions in the Balkans have failed in their purposes, and the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia could not function as a post-justice reconciliation mechanism, but rather as a criminal justice-seeking body with little influence on ethno-nationalist politicians.

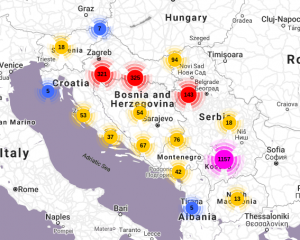

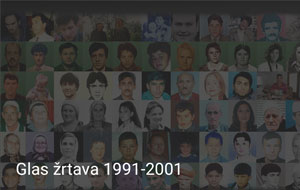

Contrastingly, the RECOM Reconciliation Network – an initiative established in 2008 – which Kostovicova examines, introduced a consultation mechanism in transitional justice. Forming a coalition, RECOM assembled approximately 2,000 human rights groups, including victims themselves, and introduced a victim-centric, fact-based, and regionally focused approach to the human rights violations perpetrated during the Balkan wars (24,25). Over 6,000 individuals from various ethnic backgrounds who were involved in the conflicts took part in the RECOM consultation process from 2006 to 2011. Herein lies the strength of Kostovicova’s work – the operationalisation of transitional justice and reconciliation, drawing from empirical insights, and employing mixed-methods approaches to understand the potential of deliberation in divided societies.

The book is grounded in a strong theoretical framework that aligns with the empirical chapters. By operationalising the concept of “deliberative democracy” and drawing on Habermas’s theory of communicative actions and Axel Honneth’s theory of recognition, Kostovicova extends a discourse-based approach to understanding solidarity and recognition in interethnic interactions within a transitional justice framework. Chapter Two focuses on the normative qualities required to deal with mistrust and polarisation in divided and post-conflict societies, as these factors could hinder “the development of an inclusive public sphere” (36). The deliberative process, even without arriving at a final decision and without the necessity for decision-making, has the potential to restore interethnic relationships (37).

“Beyond examining how people discuss war crimes, the book considers how individuals express their ethnic identities in the process of deliberation. The role of identity becomes significant in addressing the legacies of violence.”

Kostovicova’s theoretical advancements centre around examining the influence of ethnic identities during the process of deliberation (39). Drawing on the concept of identity from contact theory, she demonstrates a profound understanding of the region under study, enabling the exploration of ethnic division lines through the adaptation of a social interactional perspective on identity. This move aims to leave aside an essentialist and deterministic understanding of identity common in scholarly discourse. Beyond examining how people discuss war crimes, the book considers how individuals express their ethnic identities in the process of deliberation. The role of identity becomes significant in addressing the legacies of violence (49). Given that solely focusing on civic identities may not fully capture the dynamics of the (post) conflict, and recognising that ethnic identities are post-war constructs solidified by the violence, the analytical task is to accommodate this tension.

“Contrary to expectations, Kostovicova finds that ethnically mixed consultations exhibit higher deliberative quality than ethnically homogeneous ones.”

Thus, the research presents the factors that predict the high quality of deliberation in transitional justice consultation, such as ethnic diversity, gender, polarisation or subjectivity in rational justifications, amongst others. The quality of deliberation, while simultaneously identifying the legacies of violence, shows that identity matters during deliberation. To measure deliberation, the study employs the Discourse Quality Index adapted for transitional justice as the dependent variable; and two independent variables are developed to measure identity in discourse: first, subjectivity in rational justification, and second, storytelling positionality (78). Contrary to expectations, Kostovicova finds that ethnically mixed consultations exhibit higher deliberative quality than ethnically homogeneous ones. The findings challenge the notion that in a divided society, approaches should centre on a nonethnic discourse; it also underlines the possibility for victims – and survivors – to express their feelings of justice in post-conflict settings, launching a critique on the “monopolisation” of victims’ agency (83,84).

“Kostovicova demonstrates that deliberation in divided societies encourages questioning the hegemony of ethnocentric collective identification, which strengthens a collective narrative of victimhood.”

Chapter Five discusses the empirical approach of interactivity as an attribute of the deliberative process. Operationalising interactivity allows us to move beyond post-conflict power-sharing division. Due to the macro-level divisions, we expect a pattern of isolation or confinement of identity, labelled in the book as “ethnic enclavisation” (99). However, contrary again to expectations, agreement and respect along inter-ethnic lines in addressing the legacies of war crimes are prevalent. She demonstrates that deliberation in divided societies encourages questioning the hegemony of ethnocentric collective identification, which strengthens a collective narrative of victimhood (106). This means that deliberation advances the unlinking or disconnection between collective identities, contributing to the achievement of individuality for oneself and seeing the ‘other’ separated from their group.

“Addressing the legacies of war is not only about engaging with former adversaries but also about understanding one’s own multi-layered identity during and after conflict.”

Kostovicova’s work finds that deliberation also occurred along intra-group lines. This shows that addressing the legacies of war is not only about engaging with former adversaries but also about understanding one’s own multi-layered identity during and after conflict. This analysis brings clarity to the insufficiently understood causes and dynamics of violence and their relationship with identity, and also on the poorly comprehended legacies of mass violence and their connection with identity, self-categorisation, and victimhood.

Balkan scholars face the enormous challenge of scrutinising identity and ethnicity, aware of their intricate constructions, the influence of violence in shaping them, and the role of identity politics in their perpetuation. They must also construct an analysis that avoids replicating the conflict solely as ethnic while considering other causes of violence and its legacies, – or, better said, how to study identities in cases where, according to Brass as cited in Fearon and Laitin, violence is “socially constructed as ethnic.” With this, I aim to highlight literature (Vukosic and Kalyvas, cited in Malesevic, for example) on violence where communal violence, even if described as such, on the ground or locally, can have other motivations, such as economic ones..

The book develops a theory centred on a “discursive perspective on solidarity in interethnic interactions, a theory that places emphasis on empathy and the acknowledgement of the “ethnic Other” with the aim of bridging gaps between deliberators (46). I’m uncertain whether this approach presents a rigid understanding of identity if the source of agency or deliberation specific to individuals (victims or survivors) is linked with abstract entities like ethnic or political groups, an analysis that Balcells advanced in the micro-level explanations of the occurrence of violence. A closer and more extended theoretical examination of intra-ethnic dynamics would have enriched the analysis, further challenging collective notions of identity and victimhood in post-conflict societies.

Max Berghoz states that, “Perpetrators may imprint ethnicity onto victims through acts of violence; victims, in turn, may internalize this externally imposed ethnic categorization and, through acts of revenge, imprint ethnicity onto the initial perpetrators and those associated with them.” This raises a crucial question: when we study victims, are we truly delving into their sense of identity? This question does not aim to undermine the agency of victims but rather emphasises the need for researchers to maintain a critical distance. As Kostovicova notes, mentioning Aida Hozic, delving into the understanding and interpretation of violence in post-conflict polities “can serve the interests of those who committed genocide” (33). Hence, it is relevant to point out that this tension regarding how we analyse identity through the victim’s perspective remains unresolved.

“[The book] underscores the notion that irrespective of the duration, sustained dialogue paves the path towards reconciliation.”

The book is a humane work that positions empathy and acknowledgement as epistemological guidance. Kostovicova’s endeavour to dissect and operationalise the neglected concept of reconciliation is a brave one. Her work is an essential advancement of reconciliation and can be used within academia without compromising the integrity of the Balkan region’s history. It underscores the notion that irrespective of the duration, sustained dialogue paves the path towards reconciliation.

Ajla Henic is a Research Associate and PhD Candidate at the University of Hamburg, Germany, examining the enduring legacies of violence, memory’s role in recurring conflicts, and ordinary people’s mobilization motivations. Additionally, as a Research Associate, she investigates the lasting impact of sexual violence on gender norms. Ajla holds an MA in Nationalism Studies from Central European University and a second MA in Democracy and Human Rights from the University of Bologna and the University of Sarajevo.

This article was was originally published on blogs.lse.ac.uk.