30.08.2025.

Priority in Resolving the Fate of the Missing: Identification of Human Remains in Morgues

On behalf of the RECOM Reconciliation Network, the Humanitarian Law Center, Documenta, UDIK, and the Humanitarian Law Center Kosovo call on the governments of the post-Yugoslav countries to urgently activate existing mechanisms for resolving the fate of the missing from the wars on the territory of the former SFRY, in order to enable families to gather around the graves of their loved ones, to have a place for mourning, for family memory to become part of collective remembrance, and for the pain of losing a family member to be recognized in civil proceedings as a pain that lasts forever.

For the families of those missing in the wars, a grave is not only a physical place of burial, but also a symbolic proof of existence, identity, and dignity of their loved ones. Without a grave, families remain in a state of uncertainty and are unable to perform rituals of mourning and commemoration.

We call on governments, commissions for the missing, the Working Group on the Missing, and other mechanisms that have not been active since 2021 to dedicate the coming period to identifying more than 3,000 exhumed human remains stored in morgues in Zagreb, Rijeka, Osijek, Sarajevo, Visoko, Tuzla, Banja Luka, Mostar, Nevesinje, and Pristina.

We call on the commissions for the missing to return to the earlier practice of jointly inspecting potential locations of mass and individual graves, and to initiate verification of already exhumed mass grave sites, where, according to several sources, human remains still remain unexhumed.

It is necessary to include families in the identification process, both in the collection of additional reference samples and in establishing communication with families who have not yet reported the disappearance of their loved ones.

The Symbolic Power of the Grave

An officially marked grave is not only a place where the dead are laid to rest, but also a symbolic proof of their existence. Families of the missing, who have been denied information about the fate of their loved ones, are given through the grave an opportunity to confirm that their loss is real and that their loved ones did not simply vanish without a trace[1].

The return of human remains to families is not only a humanitarian obligation, but also an act of restoring the identity and dignity of the victim. Only when there is a grave can families perform mourning rituals and have a physical space in which the presence of their loved ones is affirmed even after death[2].

Families of the missing often repeat that they wish to find at least one bone—because that bone makes it possible for there to be a grave, a place of remembrance. That place is not only for mourning rituals, but also a testimony of history: a sign that their father, son, sister, or mother existed, and that they disappeared because of the war, not because they simply faded from memory[3].

Without a grave, families remain in a state of “ambiguous loss.” This means that the loss is present, but not confirmed. A grave has the power to transform ambiguity into fact, allowing families to begin the process of mourning and to acknowledge the reality of death[4].

Religious and cultural rituals associated with the grave provide families with an orientation in time and space. Without a grave, there is no gathering place for the community, no anniversaries, no commemorations. The grave is therefore essential not only for the family, but also for collective remembrance[5].

One of the fundamental reasons for exhumation and identification is to return the remains to the family so that they can conduct a burial. Burial restores dignity to the victim and provides the family with a place for emotional healing[6].

Mass graves are a political terrain, but for families they are above all evidence of the existence of the missing. Through exhumation and reburial in individual graves, families gain a space where they can nurture memory and preserve the truth that the person existed[7].

Data

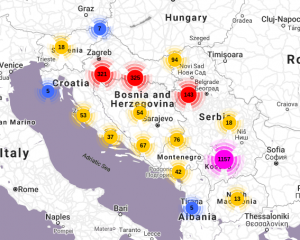

9,724 missing persons related to the wars of 1991–2000: 6,377 in BiH, 1,744 in Croatia, and 1,603 in Kosovo.

According to the data of the HLC and HLC Kosovo, which also cover missing persons whose disappearance has not been reported by their families to ICRC, the fate of another 1,614 missing persons remains unresolved.

Conclusion

A grave is not only a place of burial, but also a legal, moral, and symbolic proof that the missing once lived. It allows families to find solace and society to preserve the memory of the victims of war.

[1] Anna Petrig – The war dead and their gravesites, IRRC, 2009

[2] Grażyna Baranowska – Advances and progress in the obligation to return the remains, IRRC, 2017

[3] Eric Stover & Rachel Shigekane –The missing in the aftermath of war, IRRC, 2002

[4] Pauline Boss – Families of the Missing, IRRC, 2017

[5] Sylvain Froidevaux – Humanitarian action, religious ritual and death, IRRC, 2002

[6] Alex K. Olumbe & Ahmed K. Yakub – Management, exhumation and identification of human remains, IRRC, 2002

[7] Johanna Mannergren Selimović – The Missing and the Mass Graves, Baltic Worlds, 2023